The Eastern Cape

Department of Roads and Public works (DRPW) require material for general

maintenance of provincial roads, in particular gravel roads. There are

numerous existing borrow pits (BP’s) that have been historically used to

maintain these roads, however these are not formally registered with the

Department of Mineral Resources (DMR).

EAS was appointed

as the independent consultants to assess the environmental impacts and

requirements in terms of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act

(MPRDA, Act 28 of 2002). This includes submitting an application for a mining

right (this document), to the DMR, for the sourcing of material for

re-gravelling of roads in the area from 5 existing unlicensed borrow pits.

This EMP is prepared in accordance with the requirements of the MPRDA and DMR

Applicants for

mining permits, are herewith, in terms of the provisions of Section 29 (a) and

in terms of section 39 (5) of the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development

Act, directed to submit an Environmental Management Plan strictly in accordance

with the subject headings, and to compile the content according to all the sub

items to the said subject headings referred to in the guideline published on

the Departments website, within 60 days of notification by the Regional Manager

of the acceptance of such application. This EMP document adheres to the

standard format provided by the Department in terms of Regulation 52 (2).

The permitting will be undertaken in accordance

with the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA; No. 28 of

2002). As an organ of state, the Department of Roads and Public Works (DRPW)

has obtained exemption from the provisions of sections 16, 20, 22 and 27

(application process) of the MPRDA in respect of any activity to remove any

material for the construction and maintenance of dams, harbours, roads and

railway lines and for the purposes incidental thereto, as allowed by the said

act in section 106 (1). As such the utilisation of resources is subject only

to the preparation, submission and approval of an EMP, compiled in accordance

with the requirements of the MPRDA.

The purpose of the EMP is to identify and assess

potential impacts associated with the project through a process of

environmental investigations, stakeholder and public consultation, and to

provide sufficient detail on the project to the Department of Mineral Resources

(DMR), in order to allow DMR to make an informed decision on the project.

Exemptions from certain provisions of Act

106. (1) The Minister may by notice in the

Gazette, exempt any organ of state from the provisions of sections 16, 20, 22

and 27 in respect of any activity to remove any mineral for road construction,

building of dams or other purpose which may be identified in such notice.

(2) Despite subsection (1), the organ of state so

exempted must submit an environmental management programme for approval in

terms of section 39(4).

(3) Any landowner or lawful occupier of land who

lawfully, takes sand, stone, rock, gravel or clay for farming or for effecting

improvements in connection with such land or community development purposes, is

exempted from the provisions of in subsection (1) as long as the sand, stone,

rock, gravel or clay is not sold or disposed of.

With regard to the environment, Section 37(1) of

the MPRDA provides that the environmental management principles listed in

Section 2 of the National Environmental Management Act (No. 107 of 1998) (NEMA)

must guide the interpretation, administration and implementation of the

environmental requirements of the MPRDA, and makes those principles applicable

to all prospecting and mining operations. The NEMA principles apply throughout

South Africa to the actions of all organs of state that may significantly

affect the environment, and thus to decision making on mining

applications. These principles require that impacts on biodiversity and

ecological integrity are avoided, and if they cannot altogether be avoided, are

minimised and remedied. They also specify that the costs of remedying

pollution, environmental degradation and consequent adverse health effects and

of preventing, controlling or minimising further pollution, environmental damage

or adverse health effects must be paid for by those responsible for harming the

environment. Moreover the responsibility for the environmental health and

safety consequences of a policy, programme, project, product, process, service

or activity exists throughout its life cycle.

Furthermore, Section 37(2) of the MPRDA states

that “any prospecting or mining operation must be conducted in accordance with

generally accepted principles of sustainable development by integrating social,

economic and environmental factors into the planning and implementation of

prospecting and mining projects in order to ensure that exploitation of mineral

resources serves present and future generations”.

To ensure this, the MPRDA stipulates that:

·

the NEMA principles apply to all mining and serve as guidelines

for the interpretation, administration and implementation of the environmental

requirements of the MPRDA (Section 37(1)).

·

the holder of a permission/right/permit (Section 38):

·

must consider, investigate, assess and communicate the impact of

his or her prospecting or mining on the environment

·

must manage all environmental impacts

·

must – as far as is reasonably practicable, rehabilitate the

environment to its natural or predetermined state, or to a land use which

conforms to the generally accepted principle of sustainable development

·

is responsible for environmental damage, pollution or ecological

degradation as a result of reconnaissance, prospecting or mining operations

which may occur inside and outside the boundaries of the areas to which such

right, permission or permit relates.

·

the permission/right/permit may be issued if the Minister is

satisfied that it will take place within the framework of national

environmental management policies, norms and standards (Section 48(2)).

The MPRDA includes some key legal and regulatory mechanisms:

·

EMP: this is the main tool used to mitigate and manage

environmental impacts, detailing the proposed measures to be undertaken. The

requirements of an EMP in the MPRDA (and dependent on the

permission/right/permit to which it will be applied) are slightly different to

those prescribed in Section 24N of NEMA (Amendment Act 62 of 2008), but

generally both are giving effect to similar general objectives of integrated

environmental management laid down in Section 23 of NEMA. The MPRDA requires

mining operators to obtain environmental approval in advance of operations. It

also imposes on-going environmental management and mitigation obligations

throughout the mining life cycle. The EMP requires the applicant to undertake

an EIA (see section 3.4 for more detail) and to set out the applicant’s

financial provision for mitigation. The MPRDA (Regulation 51(a)(i)) also

requires that environmental objectives and goals for closure are included in

the EMP, highlighting the need to plan with closure in mind.

·

MPRDA Pollution Control and Waste Management Regulations: provide

that water management and pollution control comply with the provisions of the

National Water Act. It further provides that control of erosion and soil

pollution control comply with applicable legislative requirements.

·

Prohibition or restriction of mining or prospecting: in

terms of Section 49 of the MPRDA, the Minister of Mineral Resources may

completely prohibit or restrict the granting of any permission/permit/right if

the land is residential area, public road, railway or cemetery, being used for

public or government purposes or reserved in terms of any other law. This

provision allows the Minister, in consultation with other relevant Departments,

to prohibit or restrict granting permission/right/permit in certain areas of

critical biodiversity, heritage and hydrological importance.

·

In addition to the MPRDA, mining companies also need to comply

with a range of other laws which regulate mining impacts on the environment.

These include:

·

Constitution of Republic of South Africa, 1996: Section

24(a) of the Constitution states that everyone has the right ‘to an environment

that is not harmful to their health or well-being’. Mines must comply with

South African constitutional law by conducting their activities with due

diligence and care for the rights of others.

·

NEMA: Environmental management principles set out in NEMA,

and other Specific Environmental Management Acts (SEMAs) should guide decision

making throughout the mining life cycle to reflect the objective of sustainable

development25. Mining is prohibited in protected areas defined in the National

Environmental Management Protected Areas Act (No. 57 of 2003; hereafter

referred to as Protected Areas Act).

·

One of the most important and relevant principles is that disturbance

of ecosystems, loss of biodiversity, pollution and degradation of environment

and sites that constitute the nation’s cultural heritage should be avoided,

minimised or as a last option remedied. This is supported by the Biodiversity

Act as it relates to loss of biodiversity.

·

EIA Regulations (GN No. R. 543) published in terms of NEMA

trigger the need for applicants to undertake either a Basic Assessment or

Scoping and Environmental Impact Assessment if the proposed activity is

included in one or more of the three Listing Notices; and Listing Notice 3

(listing activities and sensitive areas per province, for which a Basic

Assessment process must be conducted) (GN No. R. 546).

·

In some cases both the MPRDA and NEMA require the identification,

assessment and evaluation of impacts, and the determination of appropriate

mitigation measures. An EMP may be required for activities subject to an

EIA under NEMA.

·

Water Use Authorisations: the National Water Act (No. 36 of

1998) requires that provision is made both in terms of water quantity and

quality for ‘the reserve’, namely to meet the ecological requirements of

freshwater systems and basic human needs of downstream communities. It is

essential in preparing an EMP that any impacts on water resources, be they surface

water or groundwater resources, and/ or impacts on water quality or flow, are

carefully assessed and evaluated against both the reserve requirement and

information on biodiversity priorities. This information will be required in

applications for water use licenses or permits and/or in relation to waste

disposal authorisations.

·

Mine-water regulations (Government Notice (GN) No. R. 704)

are aimed at ensuring the protection of water resources through restrictions on

locality, material, and the design, construction, maintenance and operation of

separate clean and dirty water systems. Detailed regulations on the use of

water for mine-related activities were issued in 1999 under the National Water

Act framework.

·

Liability for any environmental damage, pollution, or

ecological degradation: arising from any and all mining-related activities

occurring inside or outside the area to which the permission/right/permit

relates is the responsibility of the rights holder. This liability continues

until such time as a closure certificate is issued by the Minister of Mineral

Resources. Company directors or members of a close corporation are jointly and

individually liable for any unacceptable impact on the environment, regardless

of whether it was caused intentionally or through negligence. The National

Water Act and NEMA both oblige any person to take all reasonable measures to

prevent pollution or degradation from occurring, continuing or reoccurring

(polluter pays principle). Where a person/company fails to take such measures,

a relevant authority may direct specific measures to be taken and, failing

that, may carry out such measures and recover costs from the person

responsible.

·

Public participation: Public consultation and

participation processes prior to granting licences or authorisations can be an

effective way of ensuring that the range of ways in which mining’s impact on

the environment, social and economic conditions are addressed, and taken into

account when the administrative discretion to grant or refuse the licence is

made. Further, under Section 10 of the MPRDA, which requires that interested

and affected parties be made aware that an application has been accepted and

are given 30 days to submit comments, any objections should initiate the

establishment of a Regional Mining Development and Environmental Committee

(RMDEC).

·

Provincial legislation, such as the Land Use Planning

Ordinance (No. 15 of 1985) (LUPO) the Orange Free State’s Townships Ordinance

(No. 9 of 1969), and the Transvaal Province’s Town-Planning and Townships

Ordinance (No. 15 of 1986) which applies in Gauteng, Limpopo and Mpumalanga: to

regulate land use and to provide for matters incidental thereto. Zoning schemes

may have implications for mining and mining associated activities. Where mining

is not permitted within a zoning scheme, the holder of a mining right or permit

will need to apply for these areas to be rezoned in order to allow mining.

·

National Heritage Resources Act (No. 25 of 1999):

describes the importance of heritage in the South African context, and

designates the South African Heritage Resource Agency (SAHRA) as guardian of

the national estate which may include heritage resources of cultural

significance that link to biodiversity, such as places to which oral traditions

are attached or which are associated with living heritage, historical

settlements, landscapes and natural features of cultural significance,

archaeological and paleontological sites, graves and burial grounds, or movable

objects associated with living heritage. Further, formal protections under the

Natural Heritage Resources Act include: national heritage sites and provincial

heritage sites (some recognized globally under the World Heritage Convention),

and protected areas amongst others.

A detailed list of Biodiversity and mining related legislation includes

the following:

·

Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (No. 28 of 2002)

·

National Environmental Management Act (No. 107 of 1998), as

amended 2008

·

National Environmental Management Biodiversity Act (No. 10 of

2004)

·

National Environmental Management Protected Areas Act (No. 57 of

2003)

·

National Environmental Management Protected Areas Act (No. 57 of

2003)

·

National Environmental Management Waste Act (No. 59 of 2008)

·

National Environmental Management EIA Regulations (GN No. R. 543)

and Listing Notices 1,2 and 3 (GN No. 544, 545 and 546 respectively)

·

National Forest Act (No. 84 of 1998)

·

National Veld and Forest Fire Act (No. 101 of 1998)

·

Mountain Catchment Act (No. 63 of 1970)

·

National Water Act (No. 36 of 1998)

·

Mine-water regulations (GN No. R. 704)

·

Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (No. 3 of 2000)

·

Promotion of Access to Information Act (No. 2 of 2000)

·

Land Use Planning Ordinance (No. 15 of 1985)

·

National Heritage Resources Act (No. 25 of 1999)

·

World Heritage Convention Act (No. 49 of 1999)

·

Municipal Systems Act (No. 32 of 2000)

·

Integrated Coastal Management Act (No. 24 of 2008)

·

Marine Living Resources Act (No. 18 of 1998)

·

Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act (CARA; No 43 of 1983)

(as amended 2001)

·

Section 2(4)(a)(i): the disturbance of ecosystems and loss of

biological diversity are avoided, or, where they cannot be altogether avoided,

are minimised and remedied.

·

Section 2(4)(a)(ii): pollution and degradation of the environment

are avoided, or, where they cannot be altogether avoided, are minimised and

remedied.

·

Section 2(4)(a)(vi): the development, use and exploitation of

renewable resources and the ecosystems of which they are part do not exceed the

level beyond which their integrity is jeopardised.

·

Section 2(4)(a)(vii): a risk-averse and cautious approach is

applied, which takes into account the limits of current knowledge about the

consequences of decisions and actions.

·

Section 2(4)(e): responsibility for the environmental health and

safety consequences of a policy, programme, project, product, process, service

or activity exists throughout its life cycle.

·

Section 2(4)(o): The environment is held in public trust for the

people, the beneficial use of environmental resources must serve the public

interest and the environment must be protected as the people's common heritage.

·

Section 2(4)(p): The costs of remedying pollution, environmental

degradation and consequent adverse health effects and of preventing,

controlling or minimising further pollution, environmental damage or adverse

health effects must be paid for by those responsible for harming the

environment.

·

Section 2(4)(r): Sensitive, vulnerable, highly dynamic or

stressed ecosystems, such as coastal habitats including dunes, beaches and

estuaries, reefs, wetlands, and similar ecosystems require specific attention

in management and planning procedures, especially where they are subject to

significant human resource usage and development pressure.

1.3

Responsibilities of Role Players

1.3.1

Developer

The Developer (DRPW) remains ultimately

responsible for ensuring that the development is implemented according to the

requirements of the EMP. The developer is responsible for ensuring that

sufficient resources (time, financial, human, equipment, etc0 are available to

the other role players (e.g. the ECO, CLO and contractor) to efficiently and

effectively perform their tasks in terms of the EMP. The Developer is liable

for restoring the environment in the event of negligence leading to damage to

the environment. The developer shall endure that the EMP is included in the

tender documentation so that the contractor who is appointed is bound to the

conditions of the EMP. The developer is responsible for appointing an

Environmental Control Officer (ECO) to oversee all the environmental aspects

relating to the development.

1.3.2

Consulting Engineer

The Consulting Engineer, is bound to the EMP

conditions through his/her contract with the developer, and is responsible for

ensuring the she/he adheres to all the conditions of the EMP. The Consulting

Engineer shall thoroughly familiarise him/her-self with the EMP requirements

before coming onto site and shall request clarification on any aspects of these

documents, should they be unclear.

1.3.3

Contractor

The Contractor, as the developer’s agent on site,

is bound to the EMP conditions through his/her contract to the developer, and

is responsible for ensuring that she/he adheres to all the conditions of the

EMP. The Contractor shall thoroughly familiarise him/her-self with the EMP

requirements before coming onto site and shall request clarification on any

aspects of these documents, should they be unclear. The contractor shall

ensure that he/she has provided sufficient budget for complying with all EMP

conditions at the tender stage. The Contractor shall comply with all orders

(whether verbal or written) given by the ECO/Contract Engineer in terms of the

EMP.

1.3.4

Environmental Control Officer

The ECO is appointed by the developer as an

independent monitor of the implementation of the EMP. He/she shall form part

of the project team and shall be involved in all aspects of project planning

that can influence environmental conditions on the site. The ECO shall attend

relevant project meetings, conduct inspections to assess compliance with the

EMP and be responsible for providing feedback on potential environmental

problems associated with the development. In addition, the ECO is responsible

for:

- Liaison with relevant authorities;

- Liaison with contractors regarding environmental management;

- Undertaking routine monitoring and appointing a competent

person/institution to be responsible for specialist monitoring, if

necessary;

- The ECO has the right to enter the site and undertake monitoring,

auditing and assessment at any time, with the agreement of the Contractor,

which agreement shall not be unreasonably withheld.

1.3.5

Environmental Liaison Officer

The contractor shall appoint an Environmental

Liaison Officer (ELO) to assist with the day-to-day monitoring of activities on

site. Any issue raised by the ECO shall be routed to the ELO for the

contractor’s attention. The ELO shall be permanently on site during the

construction phase to ensure daily environmental compliance. With the EMP and

shall be ideally a senior member of the contractors management team. The ELO

shall be responsible for ensuring that all staff members are adequately trained

and aware of the EMP. The ELO shall be responsible for undertaking weekly

environmental inspections and accompany the ECO during site visits, audits or

assessments.

1.4

Approach

This

report incorporates all the information required by the Department of Minerals

and Petroleum Resources Development regulations for Environmental Management

Plans, namely:

- A

description of the environment likely to be affected by the proposed

prospecting or mining operation.

•

Assessment of the

potential impacts of the proposed prospecting or mining operation on the

environment, socio- economic conditions and cultural heritage.

•

Summary of the

assessment of the significance of the potential impacts and the proposed

mitigation measures to minimize adverse impacts.

•

Planned monitoring and

performance assessment of the environmental management plan.

•

Closure and

environmental objectives.

•

Record of the public

participation and the results thereof.

•

Environmental awareness

plan.

•

Proof of financial provision.

•

Capacity to

rehabilitate and manage negative impacts on the environment.

•

Undertaking to execute

the environmental management plan.

1.5 Limitations

EAS has prepared this report for the sole use of

the Department of Roads and Public Works (DRPW) in accordance with generally

accepted consulting practices and for the intended purposes as stated in the

agreement under which this work was completed. This report may not be relied

upon by any other party without the explicit written agreement of the

Department of Roads and Public Works and EAS. No other warranty, expressed or

implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this report.

The conclusions and recommendations contained in

this report are based upon information provided by others and the assumption

that all relevant information has been provided by those bodies from whom it

has been requested. Where field investigations have been carried out, they

have been restricted to a level of detail required to achieve the stated

objective of the work.

All items listed in EAS Standard Terms and

Conditions of Business are applicable to this report.

This report was compiled from information obtained

from the following sources:

- Numerous site visits and assessments.

•

Public participation

•

Information on the

biophysical environment (Mr Jamie Pote)

•

Geotechnical Testing of

Borrow Pit material (Outeniqua Lab EC cc.)

1.6

Applicant and Consultant Details

Table 1: Details of Applicant

|

ITEM

|

APPLICANT CONTACT DETAILS

|

|

Name

|

Eastern Cape Department of Roads & Public

Works

|

|

Tel No:

|

(040)

602 4000

|

|

Fax No:

|

(040)

602 4001

|

|

Call centre:

|

0800

864 951

|

|

Postal Address

|

Private

Bag X0022, Bhisho, 5605

|

Table 2: Details of Consultant

1.7

Report Structure

This

report is divided into 9 chapters:

Chapter

1:

Consists

of the project introduction, background and Regional Context of the mining

application and the area in which the Borrow Pits are located.

Chapter

2:

Specific

Information relating to the individual Borrow Pits, grouped per borrow pit,

addressing the following sections of the MPRDA:

·

REGULATION 52 (2): Description of the environment likely to be

affected by the proposed prospecting or mining operation

a)

The environment on site relative to the environment in the surrounding

area.

b)

The specific environmental features on the site applied for which may

require protection, remediation, management or avoidance.

c)

Map showing the spatial locality of all environmental, cultural/heritage

and current land use features identified on site.

d)

Confirmation that the description of the environment has been compiled

with the participation of the community, the landowner and interested and

affected parties,

Chapter

3:

·

REGULATION 52 (2) (b): Assessment of the potential impacts of the

proposed prospecting or mining operation on the environment, socio- economic

conditions and cultural heritage.

a)

Description of the proposed prospecting or mining operation.

i.

The main prospecting activities (e.g. access roads, topsoil storage

sites and any other basic prospecting design features )

ii.

Plan of the main activities with dimensions

iii.

Description of construction, operational, and decommissioning phases.

iv.

Listed activities (in terms of the NEMA EIA regulations)

b)

Identification of potential impacts (Refer to the guideline)

c)

Potential impacts per activity and listed activities.

i.

Potential cumulative impacts.

ii.

Potential impact on heritage resources

iii.

Potential impacts on communities, individuals or competing land uses in

close proximity. (If no such impacts are identified this must be specifically

stated together with a clear explanation why this is not the case.)

iv.

Confirmation that the list of potential impacts has been compiled with

the participation of the landowner and interested and affected parties,

v.

Confirmation of specialist report appended (Refer to guideline)

·

REGULATION 52 (2) (c): Summary of the assessment of the

significance of the potential impacts and the proposed mitigation measures to

minimise adverse impacts.

a)

Assessment of the significance of the potential impacts

i.

Criteria of assigning significance to potential impacts

ii.

Potential impact of each main activity in each phase, and corresponding

significance assessment

iii.

Assessment of potential cumulative impacts.

Chapter

4:

3.

REGULATION 52 (2) (c): Summary of the assessment of the significance of

the potential impacts and the proposed mitigation measures to minimise adverse

impacts.

a)

Proposed mitigation measures to minimise adverse impacts.

i.

List of actions, activities, or processes that have sufficiently

significant impacts to require mitigation.

ii.

Concomitant list of appropriate technical or management options (Chosen

to modify, remedy, control or stop any action, activity, or process which will

cause significant impacts on the environment, socio-economic conditions and

historical and cultural aspects as identified. Attach detail of each technical

or management option as appendices)

iii.

Review the significance of the identified impacts (After bringing the

proposed mitigation measures into consideration).

Chapter

5:

4.

REGULATION 52 (2) (e): Planned monitoring and performance assessment of

the environmental management plan.

a)

List of identified impacts requiring monitoring programmes.

b)

Functional requirements for monitoring programmes.

c)

Roles and responsibilities for the execution of monitoring programmes.

d)

Committed time frames for monitoring and reporting.

5.

REGULATION 52 (2) (f): Closure and environmental objectives.

a)

Rehabilitation plan (Show the areas and aerial extent of the main

prospecting activities, including the anticipated prospected area at the time

of closure).

b)

Closure objectives and their extent of alignment to the pre-mining

environment.

c)

Confirmation of consultation (Confirm specifically that the

environmental objectives in relation to closure have been consulted with

landowner and interested and affected parties).

Chapter

6:

6.

REGULATION 52 (2) (g): Record of the public participation and the

results thereof.

a)

Identification of interested and affected parties. (Provide the

information referred to in the guideline)

b)

The details of the engagement process.

i.

Description of the information provided to the community, landowners,

and interested and affected parties.

ii.

List of which parties identified in 7.1 above that were in fact

consulted, and which were not consulted.

iii.

List of views raised by consulted parties regarding the existing

cultural, socio-economic or biophysical environment.

iv.

List of views raised by consulted parties on how their existing

cultural, socio-economic or biophysical environment potentially will be

impacted on by the proposed prospecting or mining operation.

v.

Other concerns raised by the aforesaid parties.

vi.

Confirmation that minutes and records of the consultations are appended.

vii.

Information regarding objections received.

c)

The manner in which the issues raised were addressed.

Chapter 7

7.

SECTION 39 (3) (c ) of the Act: Environmental awareness plan.

a)

Employee communication process (Describe how the applicant intends to

inform his or her employees of any environmental risk which may result from

their work).

b)

Description of solutions to risks (Describe the manner in which the risk

must be dealt with in order to avoid pollution or degradation of the

environment)t.

c)

Environmental awareness training (Describe the general environmental

awareness training and training on dealing with emergency situations and

remediation measures for such emergencies).

Chapter

8:

8.

REGULATION 52 (2) (d): Financial provision. The applicant is required

to-

a)

Plans for quantum calculation purposes (Show the location and aerial

extent of the aforesaid main mining actions, activities, or processes, for each

of the construction operational and closure phases of the operation).

b)

Alignment of rehabilitation with the closure objectives (Describe and

ensure that the rehabilitation plan is compatible with the closure objectives

determined in accordance with the baseline study as prescribed).

c)

Quantum calculations (Provide a calculation of the quantum of the

financial provision required to manage and rehabilitate the environment, in

accordance with the guideline prescribed in terms of regulation 54 (1) in

respect of each of the phases referred to).

d)

Undertaking to provide financial provision (Indicate that the required

amount will be provided should the right be granted).

Chapter 9

9.

SECTION 39 (4) (a) (iii) of the Act: Capacity to rehabilitate and manage

negative impacts on the environment.

a)

The annual amount required to manage and rehabilitate the environment

(Provide a detailed explanation as to how the amount was derived)

b)

Confirmation that the stated amount correctly reflected in the

Prospecting Work Programme as required

10.

REGULATION 52 (2) (h): Undertaking to execute the environmental

management plan.

Existing gravel

roads subject to the proposed project in the Tsolwana Local Municipality have

been identified by the department of Roads and Public Works as being in need of

maintenance and re-gravelling. The specific roads in the abovementioned Local

Municipal Areas is the MR00638 (R344).

Gravel roads weather over relatively short periods of time and require

periodical re-gravelling. The gravel roads identified for re-gravelling display

defects such as corrugation, ravelling, and exposed oversized stones. The

roads to be re-gravelled provide access to remote villages and the poor quality

of the roads have a significant impact on the lives of the local residents as

alternative routes to nearby towns are often too far to travel and add extra

costs to travel for individuals.

In order to

re-gravel the specified roads, large amounts of material is deeded for mostly

the wearing course of the road. In some cases the material is of such a nature

that is can be grid rolled to the appropriate size, and in others the material

would be crushed due to the physical properties of the material. Quality control

of material would include blending harder materials with fines to obtain an

optimal material quality. The extensions of existing borrow pits for the

collection of materials for the specified roads is being proposed.

After a preliminary

screening of borrow pits along the MR00638

road 5 borrow pits were selected subject

to criteria including material type, location, access, surrounding land use,

slope, erosion, hydrology and overall sensitivity. Five sites were selected

along the MR00638 road. The borrow pits will be used exclusively for the

upgrade/re-gravelling of the road they are situated adjacent to.

If approved, this

EMP will be used as guidelines for the excavation of material from the proposed

borrow pits and the rehabilitation thereof.

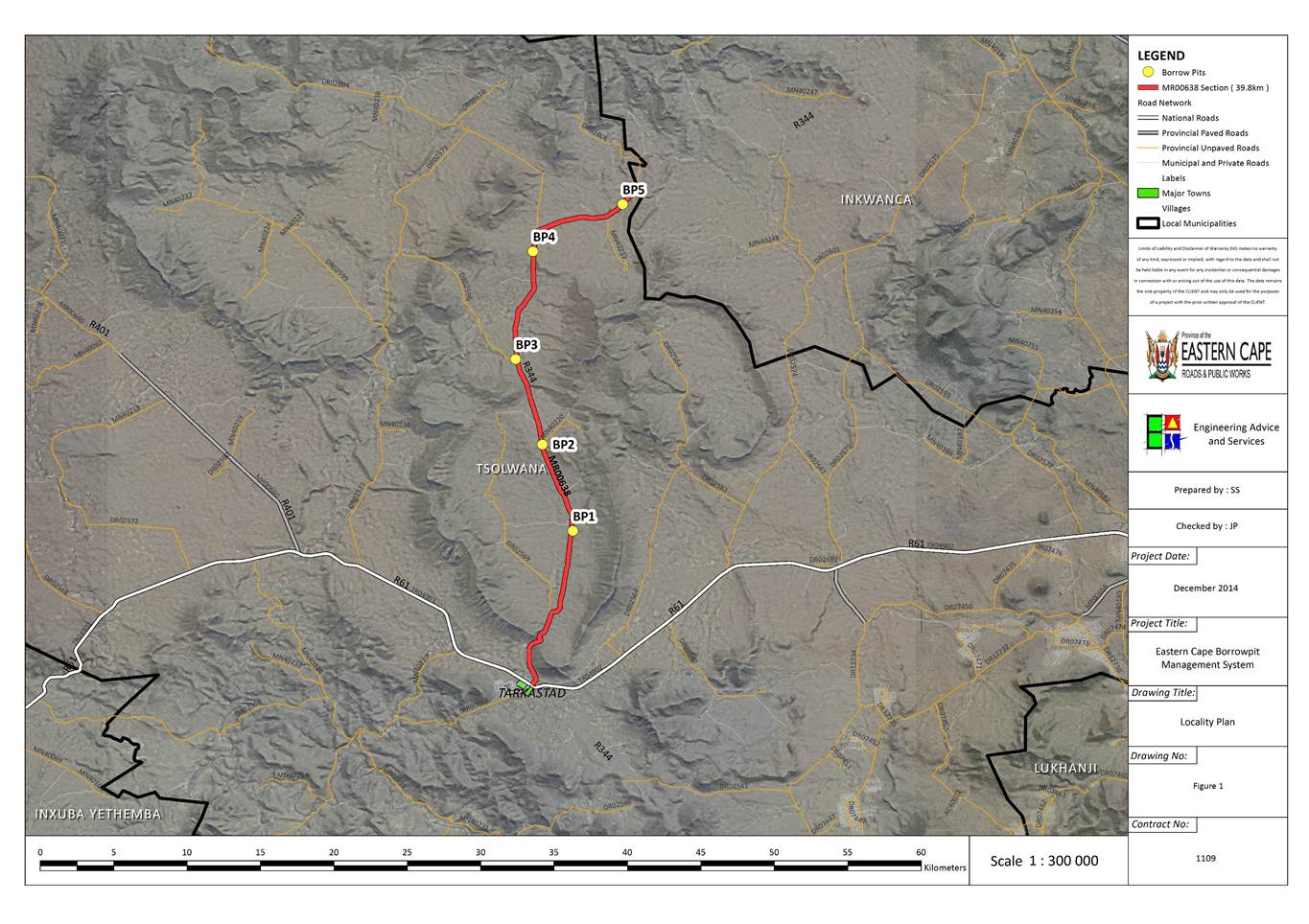

The locations of all the proposed borrow pits and

the road section they are to be used for are shown in figure 1. The affected

roads are situated north of Tarkastad along the MR00638.

Table 3: Locality of proposed

borrow pits.

|

Road

|

BP

|

Coordinates

|

LMA

|

Comment

|

|

DR02581

|

11.1

|

31.91967 S

26.30005 E

|

Tsolwana

|

|

|

|

|

16.7

|

31.87199 S

26.28068 E

|

Tsolwana

|

|

|

|

|

22.4

|

31.82505 S

26.26876 E

|

Tsolwana

|

|

|

|

|

29.8

|

31.74533 S

26.26727 E

|

Tsolwana

|

|

|

|

|

33.4

|

31.73713 S

26.3306 E

|

Tsolwana

|

|

|

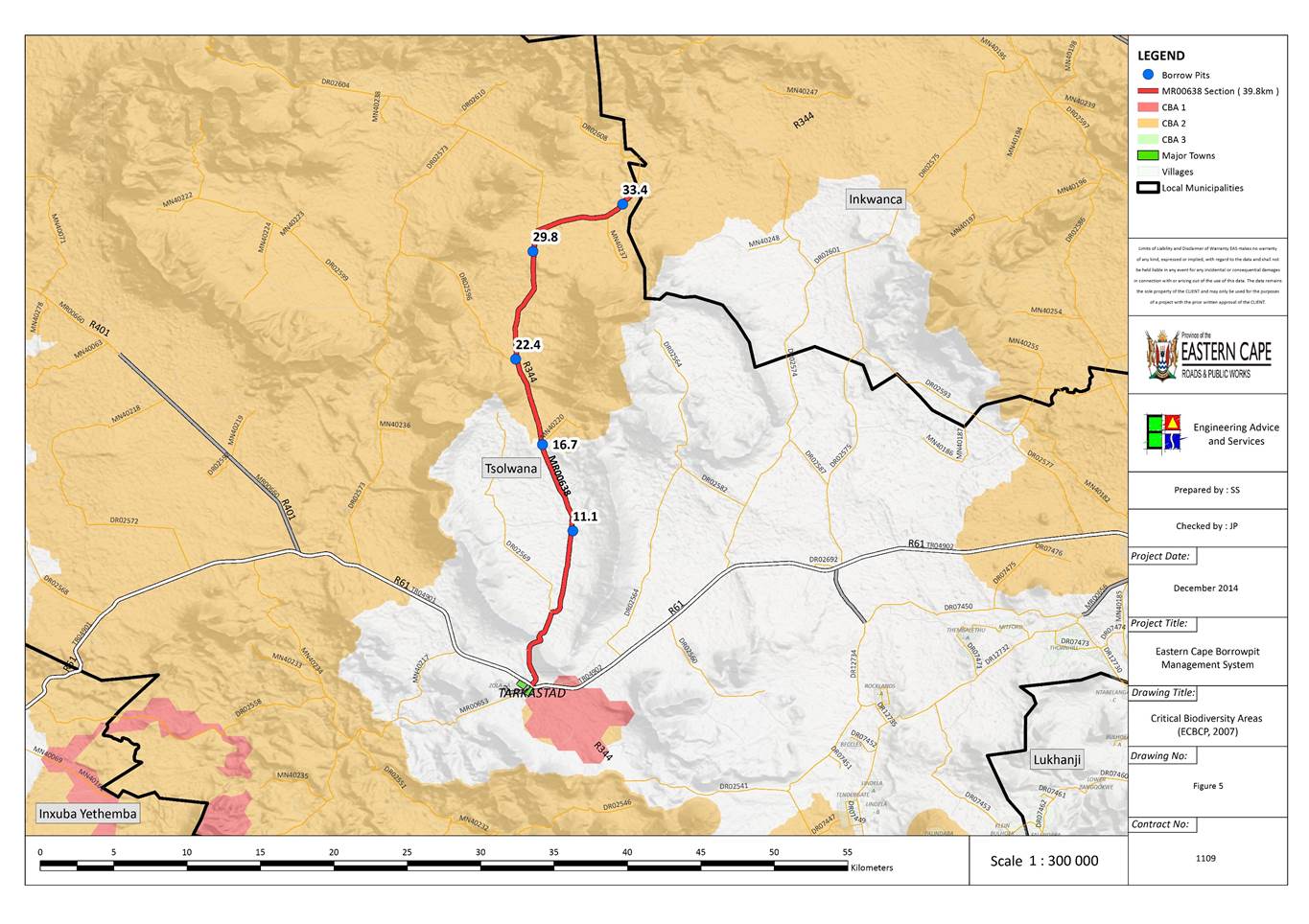

A screening of Regional Biodiversity Features was

undertaken, based on a model developed that included the following features:

·

Protected areas

·

World Heritage Sites and their legally proclaimed buffers

·

Critically Endangered and Endangered ecosystems

·

Critical Biodiversity Areas

·

River and wetland Freshwater Ecosystem Priority Areas (FEPAs),

and

·

100 m Buffer of rivers and wetlands

·

RAMSAR Sites

·

Protected area buffers

·

Trans-frontier Conservation Areas (remaining areas outside of

formally proclaimed PAs)

·

High water yield areas

·

Coastal Protection Zone

·

Estuarine functional zones

·

Ecological support areas

·

Vulnerable ecosystems

·

Focus areas for land-based protected area expansion and focus

areas.

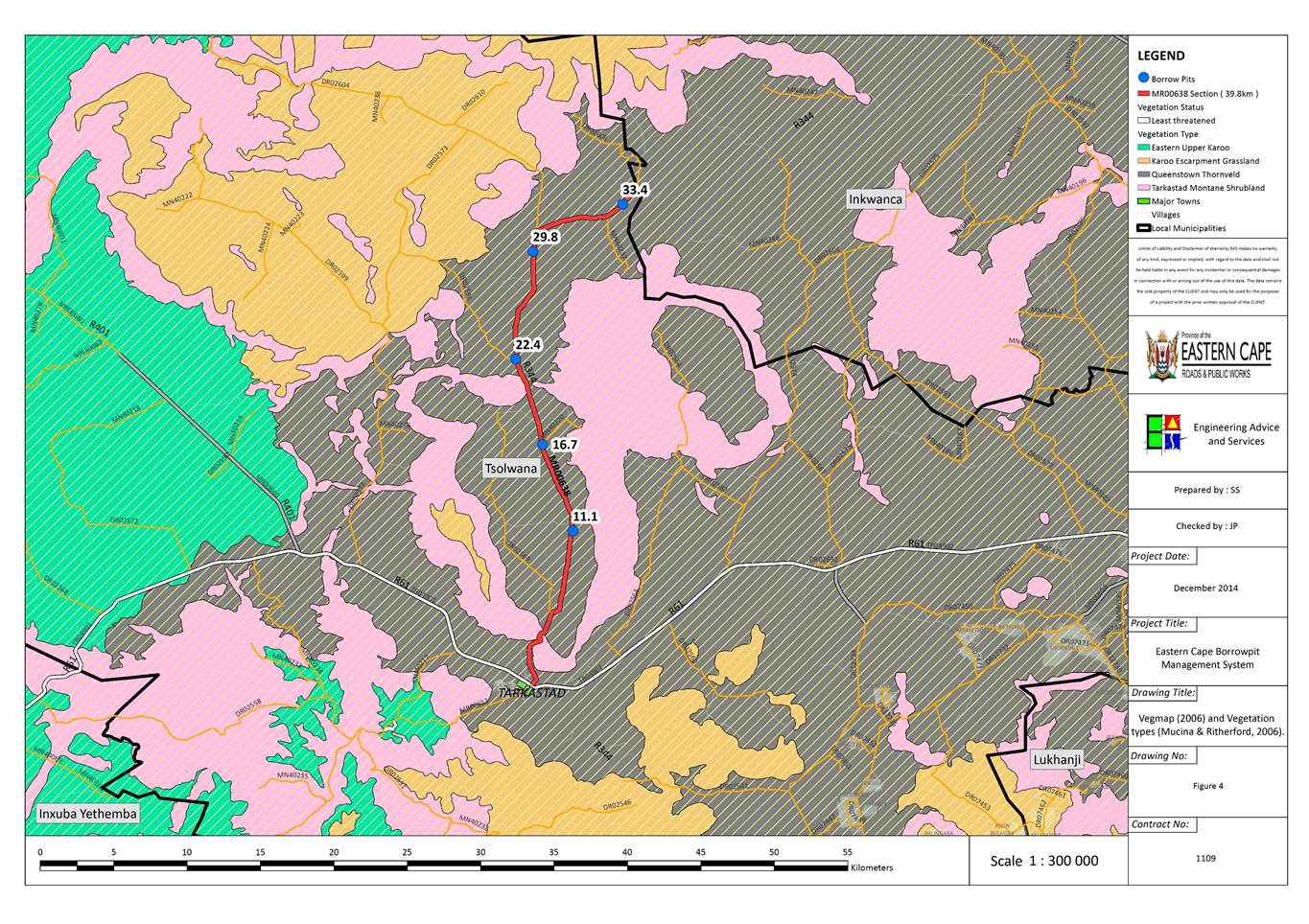

A summary of these features (illustrated in Figure 4 to Figure 6) is provided in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Summary of Biodiversity features for the Borrow Pit sites.

|

Borrow Pit

|

Vegetation Type:

|

Status

|

Present land use:

|

CBA

|

|

11.1

|

Queenstown Thornveld

|

Least Threatened

|

Natural/Grazing

|

|

|

16.7

|

Queenstown Thornveld

|

Least Threatened

|

Natural/Grazing

|

|

|

22.4

|

Queenstown Thornveld

|

Least Threatened

|

Natural/Grazing

|

CBA 2

|

|

29.8

|

Queenstown Thornveld

|

Least Threatened

|

Natural/Grazing

|

CBA 2

|

|

33.4

|

Queenstown Thornveld

|

Least Threatened

|

Natural/Grazing

|

CBA 2

|

The locations of all

the proposed borrow pits and the road sections they are to be used for are

shown in Social and economic

environment

The Borrow Pits will be utilised for routine

maintenance of gravel roads in the area. These roads connect the villages and

urban areas, thus if they are not maintained there will be a negative impact on

the people, their health (safety) and their livelihoods. Furthermore vehicular

‘wear and tear’ results in higher living costs. Formalisation of the Borrow

Pits will allow for regular routine maintenance of the roads that will benefit

not only local communities and residents but also all road users.

No people will be directly affected by the

proposed mining of Borrow Pits, but there may be a temporary noise and dust

increase on nearby residents. Potential Impacts will be assessed on an

individual Borrow Pit basis in the following sections.

There are certain risks posed to human health and safety via

exposure to high noise and dust levels, as well as steep and/or unstable faces

formed during mining activities. Pools of standing water can also pose a risk

to livestock and people in rural areas. Community health and safety risks

should be controlled through the implementation of a Health and Safety

Management Plan to be implemented by the Contractor. Existing unsafe

excavations (with vertical faces) and deep excavations where standing water can

accumulate should be “made safe” on closure using unused and stockpiled

overburden and topsoil.

Figure 1. The

affected roads are situated South-East of Cala and North-West of Engcobo.

Queenstown is located 140 km West of Engcobo and 100

km south-west of Cala (Sakhisizwe).

The surrounding area can generally be described as

flat or gentle undulating lowland plains intersected by moderately rolling

hills and mountains, much incised by river gorges. Drainage of the region is

mainly in a southerly direction.

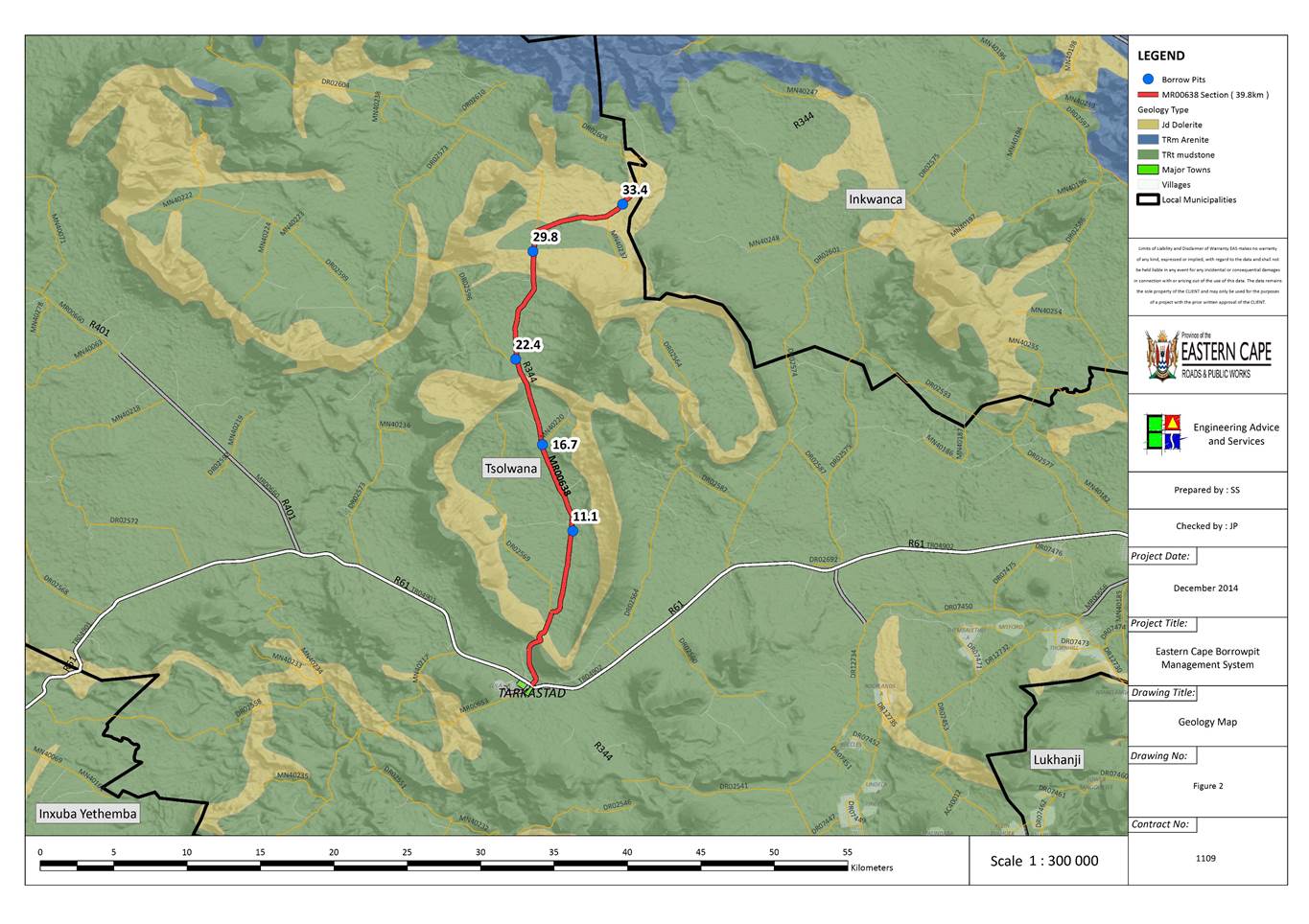

As per the Geological Map in Figure

2, the Geology in the region consists of the following:

|

Symbol

|

Lithology

|

Formation

|

|

Jd

|

Volcanic Rocks, gabbro, pikriet

|

Karroo

sequence, Drakensberg Group

|

|

Jdb

|

Volcanic Rocks, Basaltic Lava,

subordinate tuff and agglomerate

|

Drakensberg Group

|

|

TRm

|

Volcanic Rocks, Basaltic Lava,

subordinate tuff and agglomerate

|

Karroo sequence,

Drakensberg Group, Molteno Formation

|

|

TRb

|

Brownish Red

and grey mudstone, sandstone (Sedimentary)

|

Karroo

sequence, Beaufort Group, Tarkastad subgroup, Burgersdorp Formation

|

|

TRe

|

Brownish-red and grey mudstones,

sandstone

|

Drakensberg Group, Elliot Formation

|

|

Alluvium

|

Alluvium

|

|

The study area is underlain mostly by sedimentary

rocks of the Early Triassic Period Karoo Supergroup, which was formed under

fluvial conditions when the inland Karoo Sea was drying out and wide plains

were being carved by large river systems. These rivers deposited the sands and

muds on broad flood plains which over time became interbedded sandstone and

mudstone of the Katberg and Burgersdorp Formations (both of the Tarkastad

Subgroup, Karoo Supergroup).

The Katberg Formation has been mapped in the

southern and south-western part of the site and is dominated by sandstone

lithologies formed by multi-channelled braided river environments. The braided

river system resulted in the development of a deeply eroded landscape with few

fine-grained (mud and silt) overbank deposits developing. This formation

therefore consists mainly of sandstone with sub-ordinate argillaceous (rock

containing clay) maroon-coloured mudstone.

A return to a meandering river system is reflected

in the mudstone-dominated strata of the Burgersdorp Formation, which has been

mapped in the eastern and north-eastern parts of the study area. This formation

is dominated by maroon, grey and olive-coloured mudstone and is considered a

distal equivalent to that of the Katberg Formation.

These Beaufort Group rocks are interrupted by

doleritic dykes (vertical intrusion) and sills (horizontal intrusion) formed

during the Jurassic Period. These intrusions forced their way between the

sedimentary strata during the eruption phases that formed the Drakensberg Group

basalts. The sedimentary rocks into which the dolerite intruded are often

altered (metamorphosed) in aureoles adjacent to intrusions (e.g. Hornfels). The

dolerite has a regional north-south trend around which the Sabalele Road has

been constructed. This material is, therefore, likely to be intersected in

outcrop in the southern part of the study area.

Geotechnical Interpretation

The Karoo Supergroup rocks generally reveal a

subdued topography in the study area with a variable weathering profile. The

sandstone lithologies tend to be more weathering resistant and are blanketed by

a thinner soil cover than that of the softer, mudstone rocks. The completely

weathered rock/ residual soil interface is commonly susceptible to dispersion

and piping erosion, resulting in the development of the characteristic

donga-marked landscape where sloping ground prevails.

The sandstone lithologies have a rock strength

that is often considered too low for use as base course or sub base, yet it is

too high (and has little binding capabilities) for use as a crushed wearing

course on unsurfaced roads. This material is likely to require crushing for any

aggregate application. The mudstone rocks also have a rock strength that is

considered too low for use as base course or sub base. The rock is, however,

often a preferred material for gravel wearing course applications, and breaks

down easily on the roadway during mechanical placement. Most of the Karoo

Supergroup rocks are considered suitable for select subgrade applications.

The intrusive dolerites can be highly variable in

terms of rock strengths and weathering profiles. The geotechnical properties of

these rocks are often affected by the cooling rates of the magma when they were

formed; slow cooling magma forms larger crystals that develop into high

strength rocks, whilst quickly cooling magma forms smaller crystals that can

eventuate into low strength rocks. The dolerite also displays a weathering

profile that can be deep (tens of metres) and dominated by fresh rock core

stones of variable sizes, or shallow weathering with soil cover often less than

one metre underlain by competent rock without core stones. The weathering

profiles and rock strengths of dolerite are not easily ascertainable based on

surface outcrop. It is common, nevertheless, for the dolerite outcrop to reveal

a positively weathered landform in the study area, frequently associated with a

very different vegetation cover to that of the surrounding Karoo Supergroup

rocks.

The extremely weathered dolerite reveals a deep

red-coloured soil cover often pock-marked with sub-rounded and well-rounded

dolerite core stones. These weathered soils are often highly dispersive and

erosion scours are common in areas where positive relief is not offered adequate

protection from vegetation cover. Doleritic soil is frequently highly expansive

and considered unsuitable for any road construction application. The materials’

construction suitability improves with depth as the highly weathered rock

(Sabunga) is considered suitable for gravel wearing course use in arid

environments, whilst the moderately weathered, slightly weathered and fresh

rock is a well-documented source of good sub base and base course.

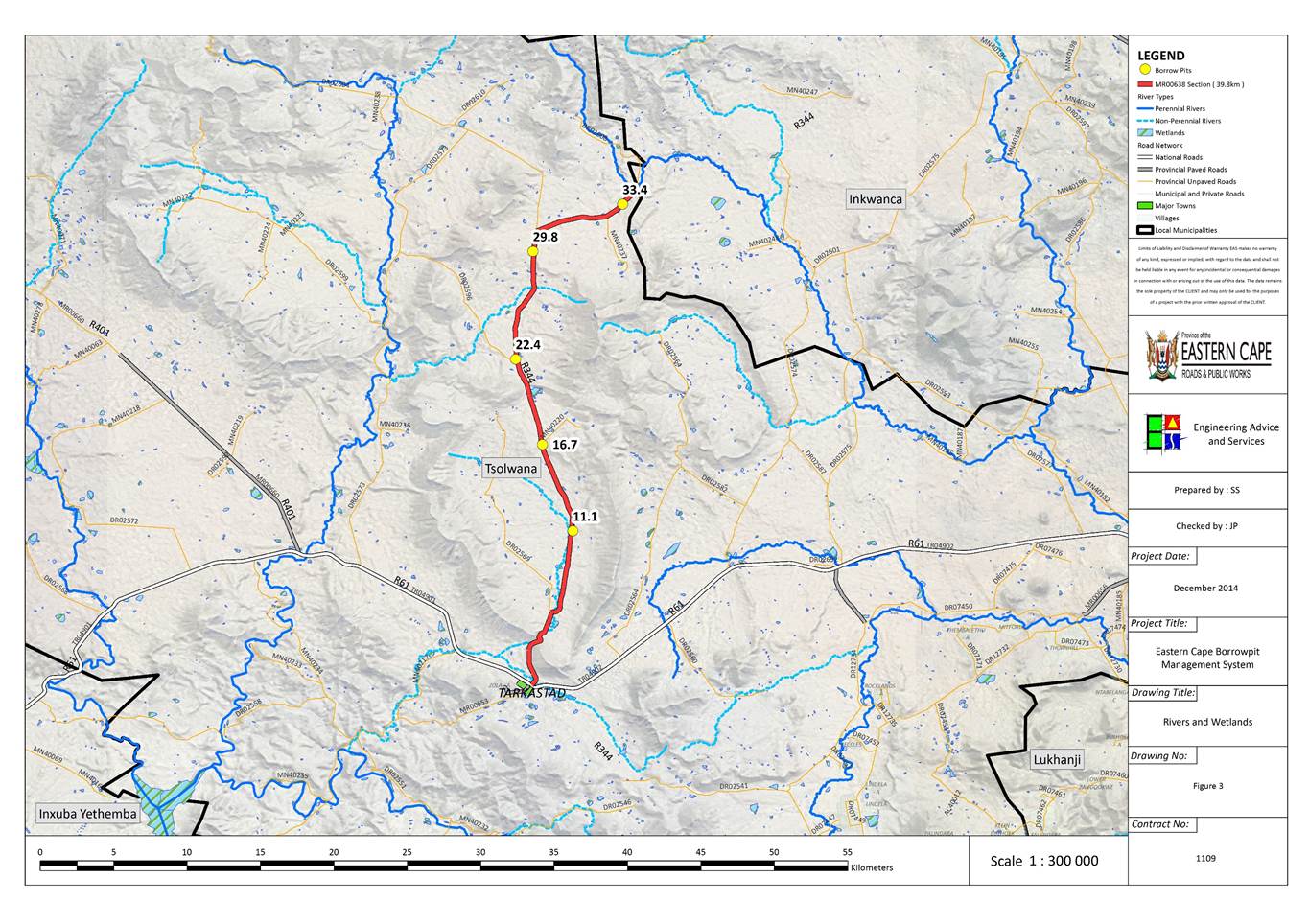

The drainage of the area generally flows in a south-easterly

direction (Figure 3). The Klaas Smits and Swart Kei Rivers are the main

drainage systems. The minor seasonal streams in the surrounding area in

proximity to the Borrow Pits are tributaries of these rivers. Where Borrow

Pits are in the vicinity of drainage lines and rivers, stormwater and runoff

will need to be adequately managed to prevent increased turbidity of downstream

river systems. With the proper implementation of the EMP it likely that any

existing impacts that are currently present will be reduced. Rivers area

indicated on the close-up maps of the individual Borrow Pit descriptions.

Some wetlands (Natural and artificial) may be in

proximity to seasonal wetlands. As for drainage lines above, runoff will need

to be managed and will be dealt with in Borrow Pit descriptions accordingly.

After rehabilitation of the Borrow Pits, some areas will probably be natural

accumulation areas for runoff from surrounding areas and become small dams or

artificial wetlands in the long-term.

Groundwater resources could potentially be

affected by the mining of Borrow pits due to inadvertent fuel and chemical

spills. If the management measure prescribed below are adhered to it is not

anticipated that groundwater resources would be significantly affected by the

Borrow Pits.

The area is a predominantly summer rainfall area.

The mean annual rainfall for Encobo (809.9

mm), decreasing westwards. Mean annual temperatures in the Engcobo area is 16.7°C

Air quality levels in rural areas surrounding the

Borrow Pit sites are typically good. The gravel roads are however a source of

dust, especially during dry windy conditions. Air quality may be temporarily

affected by the mining and concomitant road surfacing operations during the

routine maintenance periods.

The Borrow pit sites are generally situated

relatively close to provincial gravel roads, which are an existing source of

noise. The current ambient noise levels are assumed to be relatively high due

to road traffic. Noise receptors during mining operations would typically be

residents in the villages nearest to the sites.

The Beaufort Group is Late Permian (255 million

years) to Mid Triassic (237 million years) in age. Characteristic fossils

include fish, amphibians and reptiles with a dominance of mammal-like reptiles

(Theraptids). In addition, characteristic fossils include plant fossils of the

Glossopteris flora with occasional invertebrate fossils (freshwater

bivalve molluscs). Most of the fossil specimens represent groups that are now

extinct. It is estimated that less than 5 % of sites have been identified in

the Eastern Cape. There is a lack of identified sites in the District.

An internationally important record of life during

the early diversification of land vertebrate is provided by the floodplain of

the Beaufort Group (Karoo Supergroup). Giant amphibian coexisted with diapsid

reptiles (the ancestors of dinosaurs, birds and most modern reptiles), anapsids

(which probably include the ancestors of tortoises) and synapsids, the dominant

of the group of the time which included the diverse therapsids (including the

ancestors of mammals). The rocks provide the world’s most complete record of

the important transition from early reptiles to mammals.

Most plant and animals were decimated during the

end-Permian extinction event with Therapsid diversity being a serious contender

for the most severe extinction event to affect life on Earth. Ongoing research

on the effects of this extinction event is facilitated by the detailed record

(afforded by the Beaufort Group strata) of life immediately before and after

the event, as well as the gradual recovery of life afterwards.

The Beaufort Group is subdivided into a series of

biostratigraphic units on the basis of its faunal content. There is a marked

faunal change that occurs between the Dicynodon and Lystrosaurus

Assemblage Zones and approaches the tops of the Balfour Formation. This

corresponds with the major extinction event associated with the Perno-triassic

boundary. The Lustrosaurus Assemblage Zone spans the uppermost

(Palingkloof) member of the Balfour Formation, the Katberg Formation (Tarkastad

Subgroup, Beaufort Group, Karoo Supergroup) and the lower part of the

Burgersdorp Formation (Tarkastad Subgroup, Beaufort Group, Karoo Supergroup).

The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is

dominated by a single genus of dicynodont, Lyystrosaurus, which together

with the captorhinid reptile (Procolophon) characterise this zone. Biarmosuchian

and gorgonopsian Therapside do not survive into the Lystrosaurus

Assemblage Zone, though therocephalian and cyndontian Therapside exhibit

moderate abundance. Captohinid Reptilia are reduced, however, an unprecedented

diversity of giant amphibian characterises this interval.

The effect of the end Permian extinction event are

also evident in the extensive and important record of fossil plants present in

the rocks of the Karoo. Whereas faunas of the Pemian age are dominated by a

wide range of early seed plants, the Glossopteridale (which probably include

the ancestors of modern gymnosperms and ultimately angiosperms), this group

appears to have gone entirely extict during the end-Permian extinction. The

rocks of the Karoo provide an unrivalled sequential record of these change and

the diversification of other group of plants in the aftermath of the

extinction. The strata of the Karoo basin have also yielded fossils insects and

insect leaf damage of a range of ages.

Though including the uppermost level of the Lystrosaurus

Assemblage Zone, the Burgersdorp Formation largely corresponds to the Cynognathus

Assemblage Zone. Synapsid therapsid diversity does not demonstrate recovery

between the Lystrosaurus and Cynognathus assemblage zones. The Dicynodontia,

Lystrosaurus and Myosaurus are replance by Kombuisia and the

giant Kannemeyeria. Therocephalia exhibit a turnover of taxa at a

generic level, but an overall reduction in diversity. Cynodontia (Therapsida,

Synasida) alone amongst synapsids demonstrate a slight increase in genera.

These include the small advance Cynodont, Cynognathus, which together

with the Cynodont Diademodon and the Dicynodont Kannemeyeria, characterise

this assemblage zone. Eosuchid and captorhinid Reptilia are moderately common,

though showing no generic continuity with taxa of the underlying zone. Amphibia

remain diverse, though they are not as generically diverse as in the Lystosaurus

Assemblage Zone and likewise demonstrate no genus level continuity therewith.

Fossil fish reach their greatest known Karoo Supergroup diversity in the

Burgersdorp Formation (Cynognathus Assemblage Zone). Plants (Dadoxylon,

Dicroidium and Schizoneura), trace fossils (including both

vertebrate and invertebrate burrows) and a freshwater bivalve (Unio

karooensis) have also been recovered.

As Dolerite is an intrusive igneous rock, it

contains no fossils.

Archaeological remains can consist of the following:

1.

Human remains (graves, informal graves and cemeteries)

2.

Stone artefacts and tools

3.

Large Stone Features (Isisivane and circular stone walls)

4.

Freshwater shell middens

5.

Historical artefacts and features

6.

Fossil Bone

1 Human Remains

Any, and all, human remains that

are exposed during all phases of construction must be reported to the

archaeologist, nearest museum or relevant heritage resources authority.

Construction must then be halted until the archaeologist has investigated and

removed the human remains. Human remains may be exposed when a grace or

informal burial has been disturbed. Remains are either buried in a flexed

position on the side, or in a sitting position with a flat stone capping the

location of the burial. Developer are requested to be aware of the exposing

human remains.

2 Stone Artefacts

Stone artefacts can be difficult

for the layman to identify. Large accumulations of flaked stones that do not

appear to have been distributed naturally must be reported. If the stone

artefacts are associated with bone / faunal remains or any other associated

organic and material cultural artefacts, development must be halted immediately

and reported to the archaeologist, nearest museum or relevant heritage

resources authority.

3 Large Stone Features

Even though large stone features

occur in different forms and sizes, they are relatively easy to identify. The

most common features are roughly circular walls (most collapsed), usually dry

packed stone, and may represent: stock enclosures, the remains of wind breaks or

cooking shelters. Other features consist of large piles of stones of different

sizes and height that are known as isisivane. These features generally

occur near river and mountain crossings. The purpose and meaning of the isisivane

are not fully understood, however, interpretations include the representation

of burial cairns and symbolic value.

4 Freshwater Shell Middens

Accumulations of freshwater shell

middens comprising mainly freshwater mussel occur along the muddy banks of

rivers and streams and were collected by pre-colonial communities as a food

resource. The freshwater shell middens generally contain; stone artefacts,

pottery, bone and (sometimes) human remains. Freshwater shell middens may be of

various sizes and depths. An accumulation that exceeds 1

m² in extent must be report to the archaeologist, nearest museum or relevant

heritage resources authority.

5 Historical Artefact and Features

These are relatively easy to

identify and include the foundations and remain of buildings, packed dry stone

walling representing domestic stock kraals. Other items include historical

domestic artefacts such as: ceramics, glass, metal and military artefacts and

dwellings.

6 Fossil Bones

Fossil bones may be embedded in

geological deposits. Any concentrations of bone (whether fossilized of not)

must be reported to the archaeologist, nearest museum or relevant heritage

resources authority.

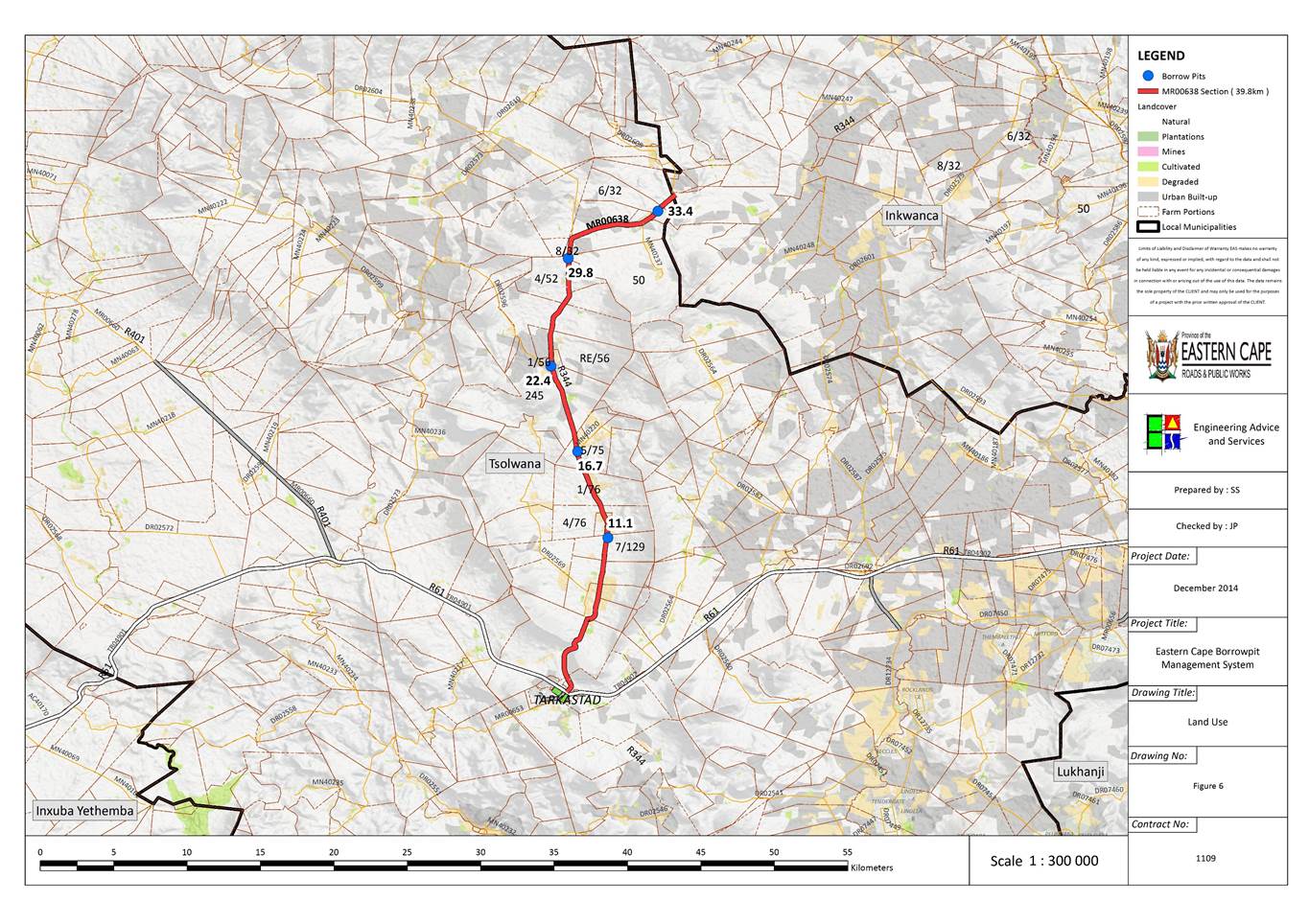

As indicated in Figure

6 the Borrow Pits are predominantly located within or adjacent to areas

classified as Degraded, Cultivated and in some cases (Peri) Urban as per the

SANBI Land Cover (2009) map.

The erosion potential of soils is the sensitivity

of soils to the effects of wind and water on the soil structure. The

erodability index is determined by combining the effects of slope and soil

type, rainfall intensity and land use. A low value indicates a high erosion

risk and a high value indicates a low erosion risk. The area falls within an

erodability index of between 7 and 9, indicating that the area has a moderate

to high susceptibility to erosion. Adequate measures must thus be implemented

to minimise erosion.

At a regional level, a single vegetation types are

recognised within the immediate vicinity of the borrow pit sites (Mucina & Rutherford, 2006), which is namely Queenstown Thornveld (Figure

4), having a conservation status of Least Threatened (Mucina

& Rutherford, 2006).

Queenstown Thornveld

Distribution ranges within the Eastern Cape from

Tarkastad to Queenstown. Typical species include: Acacia karroo thornveld

dominated by Aristida congesta, Cymbopogon pospischilii, Eragrostis curvula

and Tragus koelerioides grasses, with scattered shrubs in places.

Present on flat bottomlands of intramontane basis

with adjacent slopes. Rainfall is typically in late summer (peak in Feb –

March) with MAP 280 – 720 mm p.a.

The geology is dominated by sedimentary rocks of

the Tarkastad Subgroup (Beaufort Group, Karoo Supergroup), overlain with

clay-loam soils typical of the Da and Fc land types.

Conservation: Least threatened. Target 23 %.

Around 1 % statutorily conserved in the Tsolwana Nature Reserve. About 10 %

is transformed with overgrazing and urban expansion important factors.

2.6.12 Eastern Cape

Biodiversity Conservation Plan (ECBCP)

Critical biodiversity areas (CBAs) are terrestrial

and aquatic features in the landscape that are critical for conserving

biodiversity and maintaining ecosystem functioning (SANBI 2007). These form the

key output of the conservation plan. They are used to guide protected area

selection and should remain in their natural state as far as possible.

As indicated in Figure

5, the Eastern Cape Biodiversity Conservation Plan (ECBCP, 2007) the Borrow

Pits are situated in areas designated a CBA 2 or no status (terrestrial). Due

to the limited size of these Borrow Pits, their effect on Critical Biodiversity

Areas will be minimal. Individual Borrow Pits that are within CBA 2 areas

will be highlighted and appropriate measures recommended in the Impact and

Mitigation sections of the report where specific measures are necessary.

No Borrow Pits are located within designated

Reserves (class 1 and class 2) none are within aquatic CBA’s.

The expansion of the borrow pits is unlikely to compromise

the vegetation units significantly due to:

·

The small mining footprint.

·

The generally degraded state of the existing borrow pits and

immediate vicinity.

·

The general close proximity to the road reserves.

·

The implementation of a formalized rehabilitation plan.

Loss of vegetation cover will thus tend to be

highly localised and have a minimal impact (individual and cumulative) at a

regional level. Furthermore it will most likely result in an overall

improvement of the ecological integrity of existing sites that currently tend

to be in a highly degraded state, as a result of inadequate historical

remediation methods.

The impact of the expansion of existing Borrow

Pits, generally located directly adjacent to roads in areas that are generally

degraded is unlikely to have any significant negative impact on ecological

processes occurring at a regional level. The implementation of best practice

guidelines (as per the EMP) will most likely be effective management to

minimise any negative consequences to being located within Critical Biodiversity

Areas. In addition, since the existing Borrow Pits are currently inadequately

managed, the implementation of the recommended management actions in the EMP

will most likely result in an improvement to the status quo.

Any Borrow Pits that are significantly affected by

the Regional Planning Frameworks will be dealt with accordingly in their

relative Impact and Mitigation sections.

Based on a desktop Assessment of existing online

databases as well as field verification, the potential list of flora and fauna

species that may occur in the vicinity of the Borrow Pits, is quite extensive.

Common flora species such as: Aloe arborescens, Aloe ferox, Aloe maculata,

Bulbine abyssinica and Boophone disticha, are common around some of

the sites.

The Giant Bull Frog, may be present in wetlands,

but are unlikely to be affected by the Borrow Pits, which will not likely

impact on any wetlands.

Appendix E provides a detailed list of species

protected in term of the P.N.C.O., for which permits may be required should

they occur. However limited field assessments indicate that the majority of

these species are unlikely to be present. Due to limited sampling time, Presence

or absence cannot be confirmed without detailed seasonal site visits, but the

risk of any Critically Endangered or Endangered species being present is Low.

The limited expansion of the Borrow Pits is thus unlikely to result in any

significant impact to species conservation.

No Red Listed Critically Endangered or Endangered

species are recorded for the area.

Table 5: Species of Special Concern known to

occur in the vicinity of the sites.

|

Scientific Name

|

Family

|

Common name

|

Status

|

Endemic

|

|

Flora

|

|

Albuca setosa

|

HYACINTHACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Aloe arborescens

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Aloe ferox

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Aloe maculata

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Aristea anceps

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Bergeranthus multiceps

|

MESEMBRYANTHEMACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Boophone disticha

|

AMARYLLIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Brunsvigia grandiflora

|

AMARYLLIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Bulbine abyssinica

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Bulbine asphodeloides

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Bulbine narcissifolia

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Cyrtanthus macowanii

|

AMARYLLIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Delosperma repens

|

MESEMBRYANTHEMACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Dierama atrum

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Dietes iridioides

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Drimia macrocentra

|

HYACINTHACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Eulophia foliosa

|

ORCHIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Gasteria excelsa

|

ASPHODELACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Gladiolus longicollis subsp. longicollis

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Gladiolus mortonius

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Haemanthus humilis subsp. humilis

|

AMARYLLIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Holothrix scopularia

|

ORCHIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Hypoxis acuminata

|

HYPOXIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Hypoxis angustifolia var. buchananii

|

HYPOXIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Ledebouria cooperi

|

HYACINTHACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Ledebouria revoluta

|

HYACINTHACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Ornithogalum longibracteatum

|

HYACINTHACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Ornithogalum tenuifolium subsp.

tenuifolium

|

HYACINTHACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Ruschia putterillii

|

MESEMBRYANTHEMACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Satyrium longicauda var. longicauda

|

ORCHIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Satyrium parviflorum

|

ORCHIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Watsonia densiflora

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Watsonia pillansii

|

IRIDACEAE

|

|

PNCO

|

|

|

Mammals

|

|

Myotis tricolor

|

VESPERTILIONIDAE

|

Temminck's Hairy Bat

|

Near Threatened

|

|

|

Reptiles

|

|

None

|

|

|

|

|

|

Amphibians

|

|

Pyxicephalus adspersus

|

PYXICEPHALIDAE

|

Giant Bull Frog

|

NT

|

|

|

Invertebrates

|

|

Aslauga australis

(Butterfly)

|

LYCAENIDAE

|

Southern Purple

|

Data Deficient

|

Yes

|

|

Chrysoritis lyncurium

(Butterfly)

|

LYCAENIDAE

|

Tsomo River Opal

|

Vulnerable

|

Yes

|

|

Chrysoritis penningtoni

(Butterfly)

|

LYCAENIDAE

|

Pennington's Opal

|

Vulnerable

|

Yes

|

|

Fish

|

|

Clarias gariepinus

|

CLARIIDAE

|

|

NEMBA (NL)

|

|

The plant and animal species of special concern

listed above require permits if any individuals are to be removed, translocated

or pruned according to the relevant legislation including the National Forests

Act and the Provincial Nature Conservation Ordinance as well as Threatened and

Protected Species (T.o.P.S.)

The Borrow Pits will be utilised for routine maintenance

of gravel roads in the area. These roads connect the villages and urban areas,

thus if they are not maintained there will be a negative impact on the people,

their health (safety) and their livelihoods. Furthermore vehicular ‘wear and

tear’ results in higher living costs. Formalisation of the Borrow Pits will

allow for regular routine maintenance of the roads that will benefit not only

local communities and residents but also all road users.

No people will be directly affected by the

proposed mining of Borrow Pits, but there may be a temporary noise and dust

increase on nearby residents. Potential Impacts will be assessed on an

individual Borrow Pit basis in the following sections.

There are certain risks posed to human health and safety via

exposure to high noise and dust levels, as well as steep and/or unstable faces

formed during mining activities. Pools of standing water can also pose a risk

to livestock and people in rural areas. Community health and safety risks should

be controlled through the implementation of a Health and Safety Management Plan

to be implemented by the Contractor. Existing unsafe excavations (with

vertical faces) and deep excavations where standing water can accumulate should

be “made safe” on closure using unused and stockpiled overburden and topsoil.

Figure 1:

Map indicating locality of borrow pits with major roads, towns, etc.

Figure 2: Geology Map.

Figure 3: Rivers and Wetlands

Figure 4: Positioning of the Borrow Pits relative to

the Vegmap (2006) vegetation types (Mucina & Rutherford, 2006).

Figure 5: Critical Biodiversity Areas, as per Eastern Cape

Biodiversity Conservation Plan (ECBCP, 2007). CBA 1, 2 & 3 areas as well

as Forest pockets and Expert species data are shown.

Figure

6: Land Use – excluding Natural Vegetation (SANBI Landcover, 2006)

indicating Plantations, Degraded, Cultivated and Urban/Per-Urban areas.